Lately I have seen a slew of ads for expensive classes promising to “help you become a successful artist.” These are marketing classes, not classes in art instruction. Preying on financially strapped artists during a pandemic seemed like a new low, but clearly there must be a demand for this type of advice. So I decided to boil everything I have learned as an artist, curator, researcher, and marketer about obtaining success in the art world down into a single piece of free advice. If you want to succeed as an artist, make as much work as possible. That is the secret sauce. Regardless of whether you are after commercial success or simply want to improve in your craft, the answer is the same, make more work. If you want to know why I believe making more work improves your chances of success, read the rest of this post.

There are few sins in my book worse than encouraging artists to produce less work. It’s like telling a fish not to swim or a bird not to fly. Yet this advice is often given by dealers and gallerists with good intentions who are trying to help artists “manage” their career and avoid “flooding their own market.” We’ll never know the amount of art that was not produced as a result of this bad advice. What a crime to rob humanity of more art simply to try and artificially inflate the market value of an artist’s work. In this post, I will argue there is no evidence that producing a high volume of work in any way damages an artists’ market. If anything, producing more work likely improves their chances at success.

To study the effect of producing “too much work” on an artist’s market, we first need to establish “how much is too much?” The truth is that nobody knows the answer to this question. Five years ago, I went in search of a single database listing the total number of works created by our best-known artists. I reached out to a handful of Ivy league libraries as well as the Smithsonian, the Getty Institute, and other respected institutions asking for this database. They all came back to me with the same reply: “sadly no such resource exists.” So this leaves us all wondering, ‘How many artworks do successful artists create in a lifetime? A few dozen artworks? A few hundred artworks? A few thousand artworks? Low tens of thousands of artworks?’ The truth is, nobody knows because the resource to gauge this has never existed.

So I decided to start the Artnome database and get my own numbers by scanning through printed catalogues raisonne (books containing the official count of works for each individual artist). The chart below shows the total number of works created by 32 well-known artists to give us a general idea of what a normal amount of work is for an artist to produce in their lifetime.

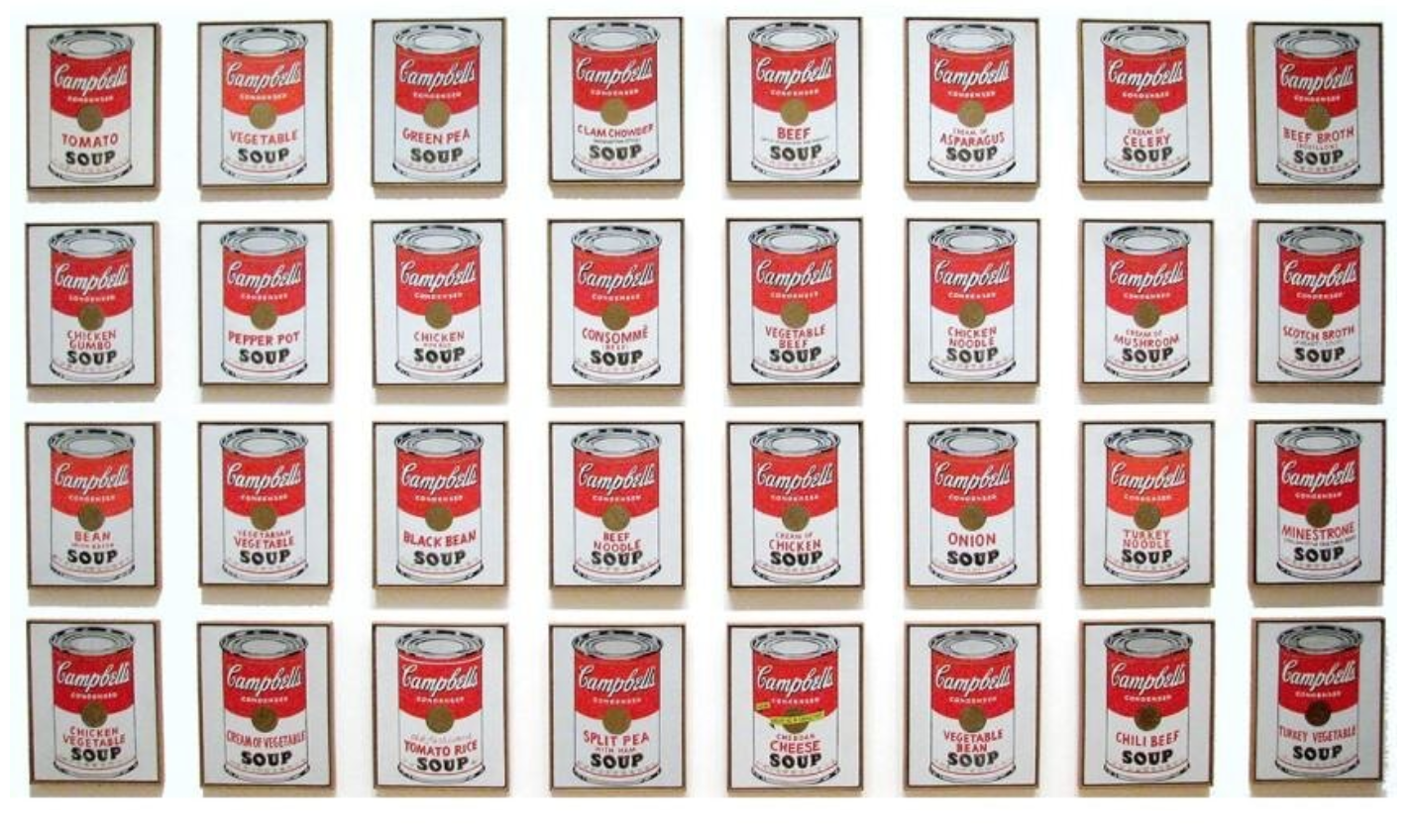

Granted, this is not a perfect measure. For example Picasso’s Zervos catalogue contains 16,000 works but that number is actually low as there are many works that are not included. By some estimates Picasso left closer to 70,000 works behind. Also, some catalogues raisonne include all works and others focus on one area such as paintings -- acknowledging the lack of absolute precision, what should immediately stand out is that Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol produced more than 10x the average amount of art produced by the other artists on the list. In fact a conservative estimate for Picasso, who lived to be 91, would suggest he created nearly one work every two days across an 80-year career. When Warhol found he could not create fast enough, he famously turned his studio into a factory and employed others to make his work for him. If anyone would have damaged their market by over-producing, it must be Picasso and Warhol, right? Let’s take a look.

Picasso’s and Warhol’s annual rank for turnover at auction vs all other artists.

ArtPrice.com puts out a report every year of the top 500 top-selling artists ranked by turnover at auction. It turns out Picasso and Warhol on average land in the top five spots over the last five years. So two of the most prolific artists of all time not only avoided “flooding their market,” but also managed to consistently rank among the top selling artists of all time. Well, they must be outliers, right? Surely living artists need to be far more mindful of not over-producing?

Not so much. Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Takashi Murakami, and KAWS all took Andy Warhol’s idea of hyper-production to the next level. While we don’t know the total number of works they will create in their lifetime, each of them has produced enough work to have sold over 100 works at auction in 2019 alone. Keep in mind, those numbers don’t include private sales, and I doubt the numbers include the thousands of pieces created through branding and mass-merchandising deals.

Perhaps the reason Picasso, Warhol, Koons, Hirst, Murakami, and KAWS all produced such a large number of artworks was simply to satisfy high levels of demand. Surely an artist whose work is not selling should not produce even more work, right?

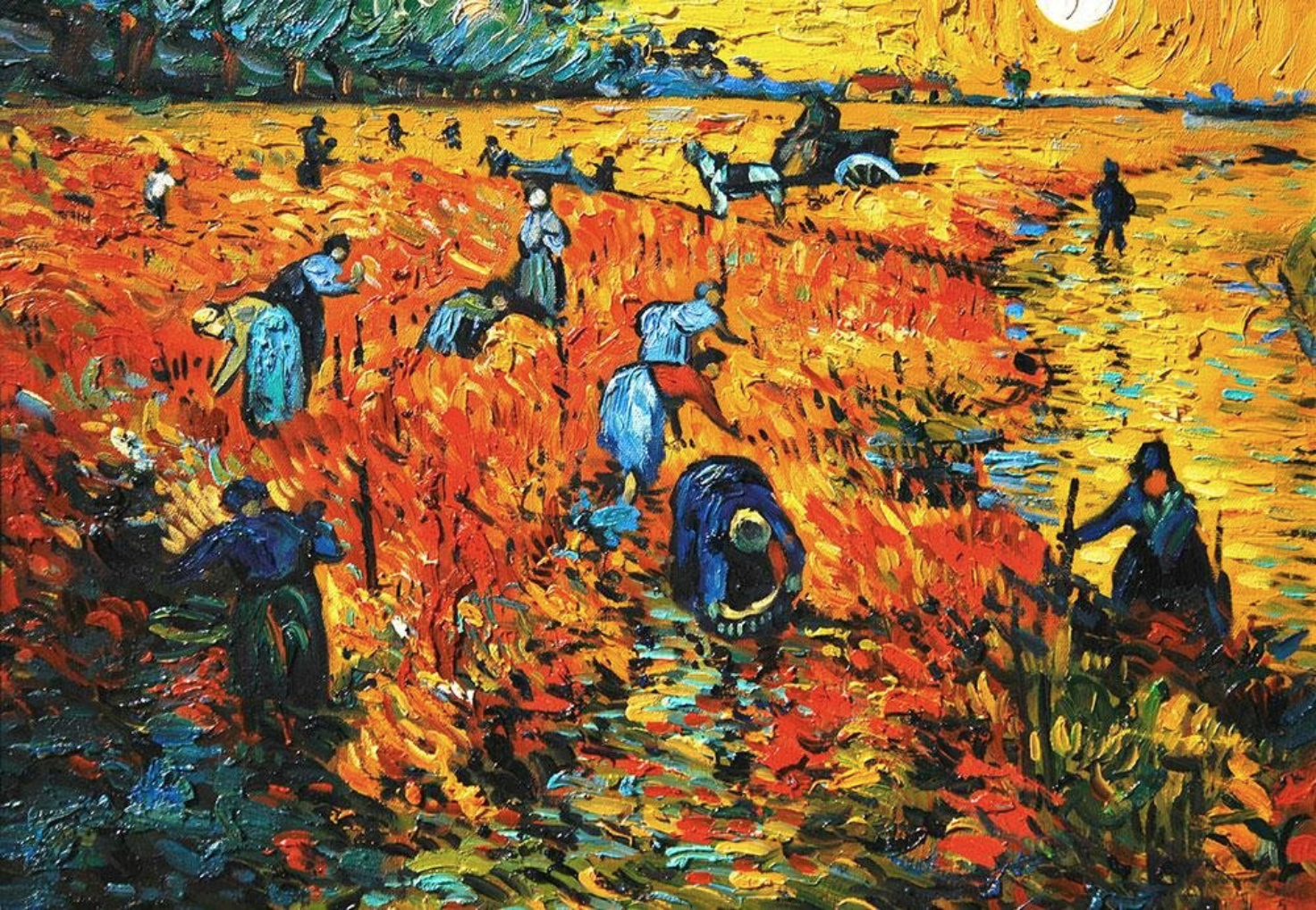

Thankfully, nobody convinced Vincent van Gogh of this. Though he got a late start to his career and tragically died young, he produced a superhuman number of paintings in a short amount of time. As one of the world’s most valued, beloved, and inspiring artists, we are lucky that he ramped up his production despite having very limited commercial success in his lifetime.

Vincent van Gogh, The Red Vineyard - 1888. The only documented sale of a Van Gogh Painting during his lifetime.

The truth is, you can’t make too much work. At least, we have yet to see an artist who has. Collectors who follow the art market closely might point to Damien Hirst. Hirst is thought by many to have flooded his own market in 2008 when he famously auctioned off 223 new works at Sotheby’s for $200.75M in 24 hours. Many argue this put a chill on Hirst’s market, but he had $26M in turnover in 2019 across 369 lots. I don’t think Hirst is suffering much.

From Hirst’s 2018 solo auction Beautiful Inside my Head Forever at Sotheby’s which net $200.75M in 24 hours

Still not convinced? After all, these are all examples of artists who have already made it. Surely there is some selection bias going on here, right? What about artists who just started out and have no market? Or up-and-coming artists just starting to build an audience who haven’t earned millions of dollars yet? Should they also make as much work as possible without worrying about flooding their markets? To find out, I asked the blockchain art market SuperRare to share data on 276 artists selling digital art on their platform. Though there is an approval process on SuperRare for artists to participate, they target artists with a very wide variety of skill and experience.

SuperRare’s equivalent of Picasso and Warhol are the artists Hackatao and Xcopy. Both artists started selling on SuperRare fairly early on and have built up a devoted collector base. As a measure of their success, they rank first and second respectively for total sales turnover (turnover in this case includes primary + secondary sales). Interestingly, their work may be “super,” but it is not particularly “rare” as compared to their peers. Both artists rank in the top 20 out of 276 artists for total works produced. So again it appears being a top producer does not limit your success, and may indeed contribute to it. Note: For more of a deep dive into what I learned from the SuperRare analysis, check out my article SuperAbundance on their new editorial site.

What about paintings vs. prints? We know that paintings are generally worth more than prints and other multiples because only one collector can claim to own a painting, whereas many can own editions of the same print. My guess is that you could indeed flood your own market by over-producing the same print over and over again. However, there are also plenty of examples of artists benefiting from repeating the same image or visual theme as a way to establish their signature or brand. Think of Shepard Fairey’s OBEY Giant image stenciled on buildings all over the world or even the instant familiarity of the concentric color squares of Josef Albers or the sliced canvases of Lucio Fontana. This combination of frequency and consistency is the core of how visual branding works in marketing, and there is no reason to believe art collectors are immune to it. However, my point in this article is not that you should make one artwork and reproduce it ad nauseum. Rather, I am suggesting you produce as many new/unique works as you like without concern that making more work will somehow damage your chances of becoming a successful artist.

Of course, success as an artist should not only be defined in terms of sales. Many artists are very successful and happy producing high quality work that they find fulfilling without ever giving much thought to selling at all. But if these artists are driven to improve at their craft over time, they too should seek to make as much work as possible. There is a famous and oft quoted passage in David Bayles and Ted Orland’s book Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking which sums up the value of quantity over quality in artistic practice:

“The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality.

His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pound of pots rated an “A”, forty pounds a “B”, and so on. Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot – albeit a perfect one – to get an “A”.

Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: The works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work – and learning from their mistakes – the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.”

Sure, this is only one example, but it rings true for many creatives (myself included). Looking for more proof that practice makes perfect? Read Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers: The Story of Success which explores the habits of extremely creative and successful people. In the book, Gladwell spends a great deal of time on the “10,000-Hour Rule,” which posits expertise in any skill is a matter of focused practice for a great many hours combined with innate talent.

Maybe you are thinking, ‘I’ve put in my 10,000 hours and mastered my craft, so why can’t I sell my work?’ Unfortunately, excellence at your craft is only part of what is required for being successful on the art market — and likely not even the most significant part. I recently wrote an article for the Harvard Data Science Review titled “Can Machine Learning Predict the Price of Art at Auction?” During my research, I was surprised to find that machine learning models designed specifically to look at the visual properties of art performed poorly in predicting value. Instead, the research suggests prestige, popularity, and access to the right network matter far more than any artistic skill or visual properties intrinsic to the artwork. Surprised? You shouldn’t be.

Pei-Shen Qian painting in the style of Mark Rothko

Collectors regularly discover that a painting they thought to be by a famous artist -- say, Mark Rothko -- has turned out to be a forgery. When this happens, paintings once thought to be worth as much as tens of millions of dollars become virtually worthless overnight. Nothing has changed about the paint, the canvas, physical condition, color, content, composition, or general artistry behind the painting. The only difference is that the painting is no longer attributable to a popular and highly sought-after artist. This puts to rest the idea that the prices paid for bluechip art are driven by the skill of the artist and the virtues of the artwork alone.

It may be depressing to realize that selling your art is largely a popularity contest. However, it can also be empowering once artists seeking to sell their work realize they have power and influence over their own success. In our digital world, artists are no longer as dependent on gatekeepers. They can and should play a role growing their own popularity and expanding their own network. Sure, you can try to accomplish this by schmoozing at all the important events, but when would you make art? Plus, a recent study suggests if you are not born with the right connections in close proximity to prestigious institutions, your chances of success are slim. The good news is, by consistently producing a high volume of work and sharing it with the world through your social channels, you can grow your own popularity, network, and collector base. Think of your art as the fuel that drives interest in you as an artist. Stop creating art and the interest will dry up; produce an abundance of work and interest will intensify.

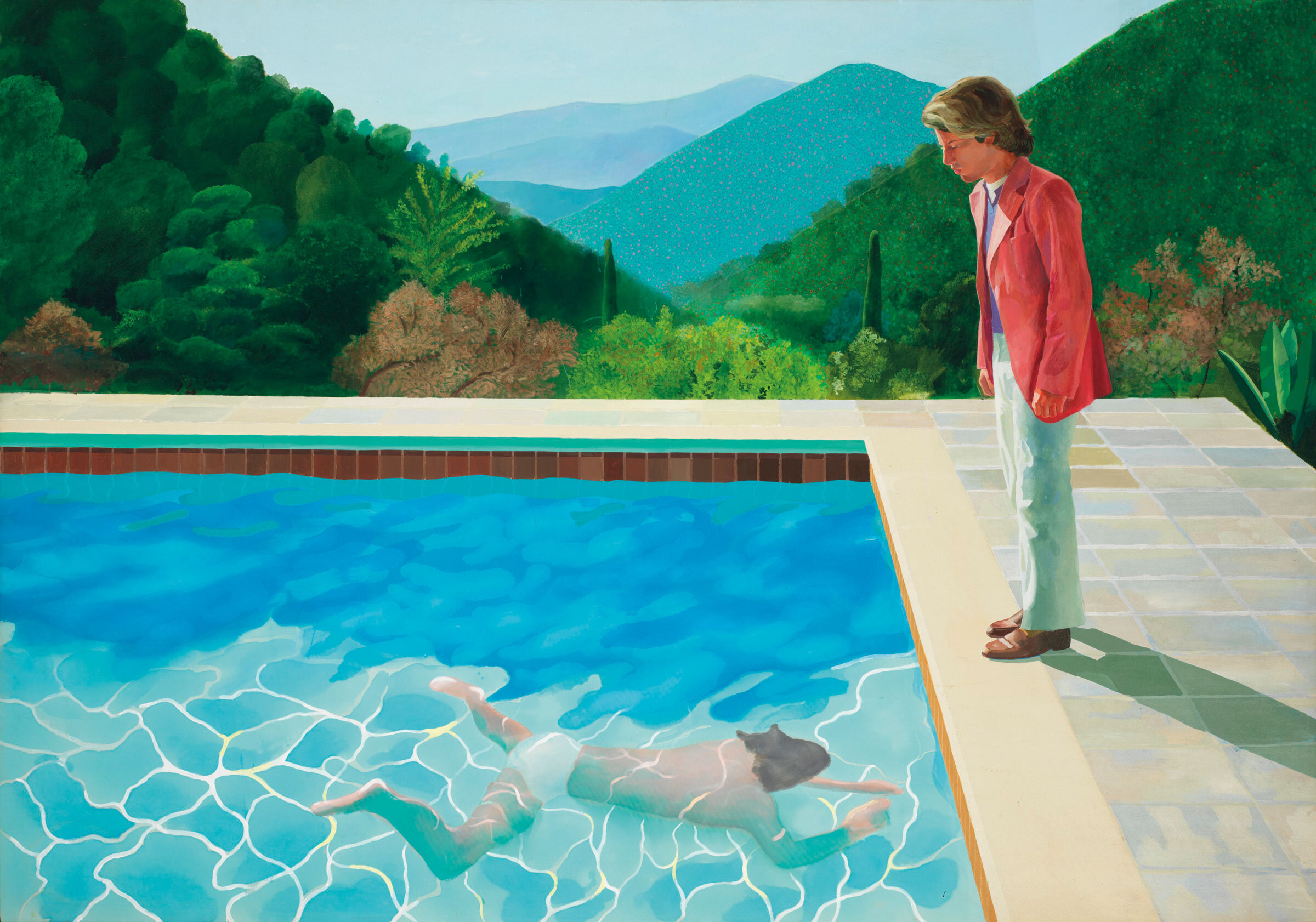

Worried about bothering people by over-sharing your work through Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, etc.? Remind yourself that Christie’s and Sotheby’s spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to make sure we see paintings like Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi and Hockney’s Self-Portrait as an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) as many times as possible leading up to their auction. They know we can’t afford to bid on paintings that sell for $100M or more. But by participating in the dialogue, we become complicit in their campaign to drive interest and value in the work. Why else would they promote these works so broadly when realistically, only a handful of collectors could afford to bid on them? The more people who see the works and the more often they see them, the more iconic and valued they become.

Pay attention to how auction houses and top galleries advertise works by top-selling artists. Do they just say, “Hey buy these paintings”? No. They tell meaningful stories about the artist and their work to help engage art lovers in the details. Follow their lead. Don’t simply flood your social feeds asking people to buy your art. Instead, try to raise the discourse by sharing works in progress, opening up about your process, and sharing the ideas behind your work. Worried about sounding too self-centered? Share work by other artists who inspire you in your feeds as well. There is a good chance they will reciprocate (though I’d encourage you to let that happen naturally).

How do I know all this works? Because I am a painfully average and introverted guy who managed to break into the art world without even trying. In the last three years, I have been invited to speak at Christie’s and Sotheby’s, commissioned to write the cover story for Art in America, and curated art exhibitions and spoken at events around the world from the US and Europe to China and the Middle East. All of these opportunities and more came from my blog. It didn’t happen right away. I wrote for six months or so before anyone cared. But consistently putting out posts led to an amazing world of opportunity and a large audience of thoughtful, culturally aware, and engaged readers. Each time I put out a new article, another door opens. My world expands, making my life much richer. If it worked for me, I’m more than certain the same can be true for you. Go make your work, don’t worry about over-producing, share it in meaningful ways, and enjoy the ride!