As many readers will be aware, 2021 saw the introduction of NFTs into mainstream conversation, which has also gripped the arts sector and encapsulated the minds of artists, collectors, and even museums. NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are a type of token stored on a blockchain that enables us to store assets such as artwork, and they can act as a certificate of authentication and ownership in the digital space. In this way, NFTs build a form of ‘digital thingness’ into digital artwork by giving if a form of identification and proof of ownership.

This ‘digital thingness’ is also understood as creating value in digital artwork, which enables the work to be commoditised. Monetisation, however, is only a by-product of blockchain, and this digital thingness offers far more than simply a way to make money. For example, my work with the National Museum Liverpool (NML) explores what alternative forms of value might be formed from engaging with NFTs in museums, and as I have been researching this space, it has become more evident that there is a need to consider what makes a museum NFT unique or different from the average crypto art NFT.

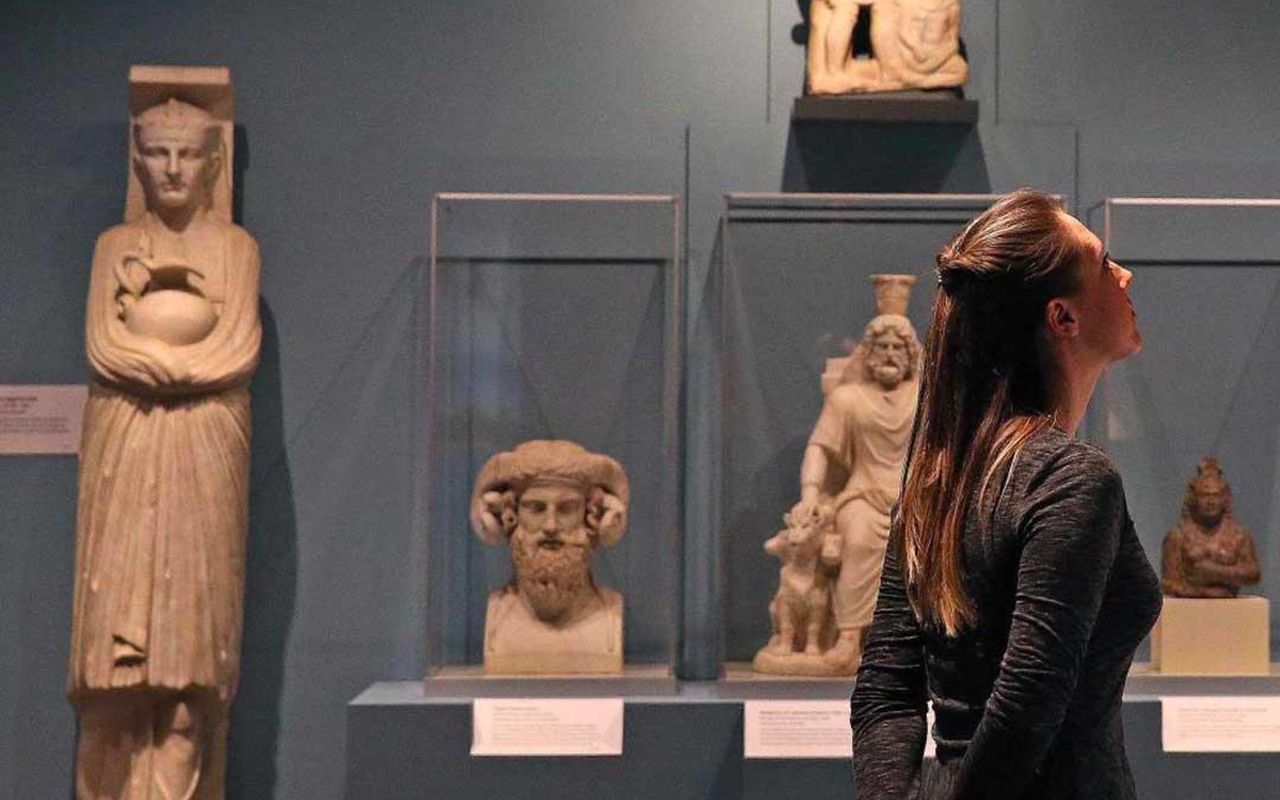

Museums are important spaces; they are stewards of culture and history, they provide interpretation, understanding, education, entertainment, and can even support stronger communities and social cohesion. Therefore, I think it is important that museum object NFTs are more than commodities to be bought and sold; they should offer more than simply monetary value. Based on this premise, I want to consider the following: what makes a museum object NFT valuable beyond the application of blockchain technology? By examining this question, I wish to highlight some of the factors that museums might want to consider as they begin to experiment with blockchain technology.

The NML Project

My research with the NML explores how we might use NFTs in museums to create a sense of shared ownership and forge connections between a museum and the audience it serves. In brief, this has involved working with a group of participants over two workshops (January and July 2020), where we co-created an online exhibition called Crypto-Connections and produced NFTs developed from the digital images from this exhibition.

The initial workshop took place in January 2020 and we invited the participants to choose a personal possession and museum object based on their personal connection. These objects formed the basis for the Crypto-Connections exhibition where each object is displayed alongside a summary written by the participant explaining why they chose that particular work. Each image from the exhibition was transformed into an NFT using a specially devised decentralised gallery called ‘The Possession Gallery’, which is connected to the Ethereum blockchain through a smart contract. Any token created using this smart contract would appear in both this decentralised gallery and the new owner’s wallet, hence, the Possession Gallery is a space that depicts all of the tokens together.

Quartz Rock - An example of an NFT from the project displayed in the Possession Gallery

I often keep some kind of rock with me, especially ones with quartz running through them. I like to imagine them as liquid in their deep past and running my thumb over something that has been shaped by wind and the sea grounds me when I’m feeling like time is perhaps moving a little fast. The lines around this particular one seems vibrational; growing from the centre and acting like a reverberation of the stone’s shape. It shouldn’t be this perfect but somehow, that’s how it was knocked about on the sea floor and dragged up onto the beach. Its beauty exists as evidence of relentless violence. - Participant 8

During a second workshop in July 2020, each participant received a token that represents their chosen objects from the exhibition and their personal story permanently attached to the token. In doing this process, I explore in my research to what extent these tokens can help to digitally bind the participants to the museum, which, in turn, adds a new layer of value to the process of community engagement in museums.

A Personal Touch

What I like about this is that it gives you an added layer of history to something, as it were, or you know an interpretation that you don’t get in a gallery space and that for me is the most important part of it.

(Participant A, Workshop 2, July 2020)

My work takes a participatory design approach, which fosters a more democratic model to the development process by working with participants in co-creating content, and this enables individuals to embed their voice into the project. In doing so, this shifts a museum visitor from being a passive viewer to an active participant whilst also creating content, exhibitions, and interpretations that feel more relevant to museum audiences (Simon, 2010). Participatory approaches also leverage shared authority as cultural institutions need to relinquish some of its control over the process of design or interpretation (although this process of sharing control often remains problematic see Davies, 2010; Lynch and Alberti, 2010; Frisch, 2011). Nevertheless, there is value in taking such an approach because it encourages participants to invest in both the project and the cultural institution, and this has the potential to harness a greater sense of belonging and produce content that is more resonate than the current, and often singular, narratives told through museum collections.

In the case of the NML project, the application of blockchain adds a new layer to co-production as the participants gain a token that depicts their personal contribution to the project. Indeed, the NFT is a representation of their personal connection to the museum object, which no one else owns. Therefore, the addition of blockchain creates an economically valuable token that also feels like a possession because the embedded interpretation creates personal value.

As museums begin their NFT journey, I think co-production will be a significant factor in NFT value creation because this process allows museum objects to be layered with new forms of interpretation that are not normally evident in the physical gallery space. Indeed, interpretation is an important part of a museum’s role as a steward of its collections because it brings context and understanding to cultural artefacts and artwork, as such, interpretation also helps us to distinguish a museum-based artefact from an artefact being sold as a commodity in the art market. In the same way, museum object NFTs will need to hold some form of interpretation to help identify it as a museum-related object rather than simply another commodity in the NFT space. Therefore, taking a participatory approach to interpretation has the potential to make more personal NFTs that also depict a more diverse set of perspectives about the original museum objects.

The Museum’s Authority

Clearly the authority and credibility of the digitising institution will play a critical role in validating digital data just as it does in preserving and relaying data associated with material objects.

(Knell, 2016, p. 4)

This above quote from Simon Knell’s book on contemporary collecting highlights another important point of value creation; the museum itself. Museums have always been considered to be in ‘the authenticating business’ (Burton and Scott, 2003, p. 58), in other words, by accessioning objects into their collections, museums validate these objects as significant forms of culture and heritage.

This idea of validating culture is a significant point when it comes to the digital space and the debate that came out of the Global Art Museum (GAM) social experiment in March 2021 only reinforces this point. In brief, GAM initially promoted on Twitter that they were listing public domain works from four museums with open data policies on the OpenSea token exchange without seeking the permission of these museums. This raised interesting questions on Twitter about the ethics of tokenising NFTs without a museum’s permission, and open data policies in museums (see Liddell, 2021), but this also raises an interesting point about the museum as an authenticator of NFTs.

GAM stated that they were never going to sell the NFTs listed on OpenSea, but, in my opinion, these NFTs would not have a sale value anyway because they were minted without the permission of the original museums. In other words, these NFTs do not hold an exchangeable value because the original museum did not ‘validate’ them. Of course, this compares the museum as a form of miner who adds a layer of authentication to NFTs that cannot be derived from blockchain technology and this power stems from the authority cultural institutions hold over their collections because, and as mentioned earlier, museums are stewards of their collections.

The same can be seen with my research where the NFTs created are closely entwined with the NML because the process worked collaboratively with the museum to co-create the NFTs. Therefore, the role of the NML is to reinforce an authenticity in these tokens and provide these NFTs with a ‘stamp of approval’ that cannot be ascertained through the technology.

As the art NFT space develops, I believe that it will be increasingly important that cultural institutions use their authority and their reputation as a body of trust to create NFTs that can also be trusted. Blockchain supports a ‘trust-less’ system of exchange and an authenticity in digital objects, but this discussion indicates that traditional authorities such as museums also play a role in informing the integrity and authenticity of NFTs. In this respect, blockchain technology cannot do away with traditional authorities and instead the two could support one another to create multiple forms of authenticity in digital object and this, in turn, could build a stronger NFT digital art space.

Translating Value

The factors discussed so far, however, are dependent on the participant’s views on the digital. For example, the second workshop in July 2020 highlighted an interesting discussion on the role of NFTs in preserving the physical objects and in this discussion a couple of the participants noted how the NFT could be a symbol of the object and their personal story if the original were lost or stolen. This indicates that the NFT is a potential store of personal value which the participant will activate if and when the physical is no longer accessible, and this suggests that the value created through blockchain is meaningless unless the physical counterpart cannot be access.

Of course, this holds resonance with the actions of the company Injective Protocol who bought a Banksy artwork and turned it into an NFT only to then burn the physical piece. In doing so, they argued that ‘the value of the physical piece will then be moved onto the NFT’ (Ennis, 2021). Likewise, the participants in my research see the potential value in the NFT if they were no longer able to access the physical counterpart, which raises the following: will we only value museum object NFTs if we can no longer access the physical original? And how might museums go about addressing this perspective on value?

These questions highlight how we still prioritise the physical experience over the digital, which might seem like a barrier to the application of NFTs in museums, but I also wonder if this could be a new space for investigation. Museums holds thousands of works in their collections many of which are too fragile to be put on display; could the NFT be a way of displaying these works and offer individuals a way to interact with them that is impossible to do in the physical gallery? This would mint an NFT that is like a museum object in its own right and it would hold a unique value because it would encourage visitors into new forms of engagement with the collections whilst also providing a way for museums to address this tendency to prioritise the physical over the digital.

What Makes a Museum Object NFT Valuable Beyond the Scope of the Technology?

While blockchain produces value, clearly, there are many more factors to consider in the process of minting NFTs in museums. Participatory approaches engage in the production of personal and social value in museums and blockchain could add a new layer of value to this process by creating ownable and more personal digital objects. Meanwhile, museums could also play a critical role in adding a new layer of authenticity in the NFT space because these institutions could use their authority as authenticators of culture to embed trust and authenticity into digital artwork, thereby creating a store of value in NFTs that cannot be gained from using blockchain alone. As such, the cultural institution and blockchain technology are both authenticators and could interplay with one another in the digital space to create more meaningful and trusted digital cultural objects.

These factors are also contingent on the participant viewing the digital object as a valuable asset, and as I have suggested, museums could strategically use NFTs as a way to present works that cannot be displayed in the physical world. In doing so, this would address the tendency to value the physical over the digital and create NFTs that are like entities in their own right that also allow museum visitors to engage with the museum object in a new way that does not harm the physical object stored in the museum.

In this respect, it is important to remember that cultural institutions are also ‘value producers’ when it comes to minting NFTs, but this value is more social, cultural and institutional in nature, and, as the field develops, I look forward to seeing how these two ‘value producers’ will forge new connections and develop understandings of value in the cultural sector.

References

Burton, C. and Scott, C. (2003) ‘Museums: Challenges for the 21st Century’, International Journal of Arts Management; Montréal, 5(2), pp. 56–68.

Davies, S. M. (2010) ‘The Co-Production of Temporary Museum Exhibitions’, Museum Management and Curatorship, 25(3), pp. 305–321.

Ennis, P. J. (2021) ‘NFT art: the bizarre world where burning a Banksy can make it more valuable’, The Conversation. Available at: http://theconversation.com/nft-art-the-bizarre-world-where-burning-a-banksy-can-make-it-more-valuable-156605 (Accessed: 19 March 2021).

Frisch, M. (2011) ‘Sharing Authority Through Oral History’, in Adair, B., Filene, B., and Koloski, L. (eds) Letting go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World. Philadelphia: The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, pp. 126–137.

Knell, S. J. (2016) Museums and the Future of Collecting. Florence, UK: Taylor & Francis Group

Liddell, F. (2021) ‘“Disrupting the Art Museum Now!”: Responding to the NFT social experiment’, Cultural Practices. Available at: https://culturalpractice.org/disrupting-the-art-museum-now-responding-to-the-nft-social-experiment/ (Accessed: 10 April 2021).

Lynch, B. and Alberti, J. (2010) ‘Legacies of prejudice: racism, co-production and radical trust in the museum’, Museum Management and Curatorship, 25(1), pp. 13–25.

Simon, N. (2010) The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, California: Museumz.